The second summer of love 30 years ago kickstarted the biggest cultural shift in the country since punk. ANDREW WOODS has his glowsticks at the ready to chart a course from Chicago to Ibiza to Manchester… and the M25.

In the summer of 2002, Anthony H Wilson – boss of Factory Records and its legendary Manchester nightclub the Hacienda – was holding court before a press screening of 24 Hour Party People; Michael Winterbottom’s musical homage to the north-west city and its music.

Wilson posited his theory that great musical movements happened once every 13 years or so. The British explosion of the early 1960s. Punk in the second half of the 1970s. And then, in 1988, the paradigm shift which took his Hacienda from an empty, costly barn to a packed, sweaty money machine – rave culture and its accompanying soundtrack.

They called it acid. Or acid house. But before that there was just house music.

Named after the Chicago club The Warehouse, house had become a catch-all term for technologically-constructed minimalist disco with repetitive 4/4 beats and a bpm of 120+.

Tracks produced by the likes of Frankie Knuckles, Marshall Jefferson and Jamie Principle sparked the interest of many UK DJs, label bosses and promoters from 1986 onwards; the year Man 2 Man Meets Man Parrish hit No.4 over here with Male Stripper. That same year, Farley Jack Master Funk entered the top 10 with Love Can’t Turn Around. 1987 saw Steve ‘Silk’ Hurley hit No.1 in the UK with Jack Your Body – a track he didn’t even bother promoting – while Pump Up The Volume by UK collective M/A/R/R/S also claimed the top spot. Something was brewing.

The squelching bass that came to typify acid house had been created after extensive experimentation by Chicago’s DJ collective Phuture. The Roland TB-303 ‘bass sequencer’ famously arrived with zero instructions and it was while fiddling with the knobs that DJ Pierre and DJ Spanky unearthed the famous bass line that instantly evoked images of bubbling lava lamps and kaleidoscopes.

phuture’s Acid Tracks (recorded in 1985 by Pierre, Spanky and Herb J and later released in 1987) was widely heralded as the first acid house single and was pushed heavily at the time by legendary Chicago DJ Ron Hardy.

UK DJs like Trevor Fung had been playing a lot of the US sounds on the Balearic island of Ibiza as far back as 1985 and he would return to the UK each autumn to play out these tracks at various clubs including The Garage in Nottingham, run by Graeme Park, and London’s Project, which Fung and Paul Oakenfold put on, with minimal success. However, 1987 saw big changes in Ibiza when a new drug popped up in this spiritual nexus of the European hippy trail.

The story goes that there was a lads’ holiday to Ibiza involving Paul Oakenfold, Nicky Holloway, Danny Rampling and Johnny Walker which hooked up with Fung and Ian St Paul, who lived on the island. The vibe that year, the friends noted, had changed significantly thanks to these little white pills. Light bulbs were duly illuminated once the loved-up group witnessed Argentinian exile DJ Alfredo mixing big anthemic rock tracks by Simple Minds and The Waterboys with Balearic beats and obscure instrumental montages at Amnesia. The friends knew they had to try and replicate that Balearic vibe back home in London, and planned club nights aimed initially at the thousands of Brits returning home from working holidays on the island.

Oakenfold launched Future in London in 1988, followed by Spectrum and Holloway started Trip. Legend has it that patrons were given a free E on entering Spectrum that first night, which saw ten times the number of ravers for the second party. But it was Danny Rampling’s Shoom – operating out of a Southwark gym – and the yellow smiley face it had appropriated from the first summer of love via Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen comics that perfectly encapsulated this rather amorphous collection of disparate influences and sounds that, while under the influence of this now readily-available drug, seemed to make some gorgeous sense.

Not far from Shoom was another influential south London club night, RIP at Clink Street, which kept with the harder sounds of acid house. Soon, UK acts such as S’Express, Coldcut and Evil Eddie Richards (performing under the name Jolly Roger) were shifting serious units of this vibe-heavy sound as pills were popped up and down the country.

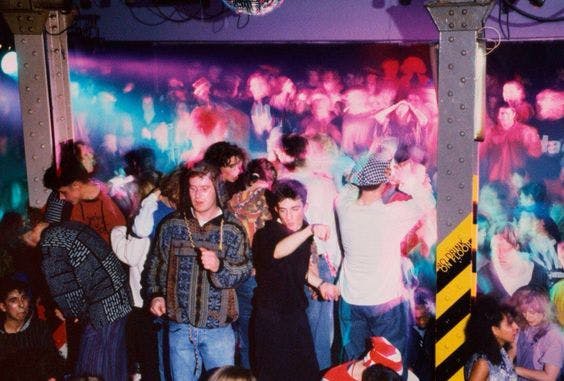

Raves were now sprouting up all over the UK as the diet-suppressing MDMA of ecstasy gripped the nation’s youth, while elevating the scene to a point where visiting DJs from the States were now shocked to see how the usually restrained Brits were now reacting to their music with whistles, glowsticks and airhorns filling the night. The ‘orbital parties’ that lined London’s M25 and the Blackburn raves in Lancashire, were the most notable of the new illegal parties, as crowd numbers started to get into the tens of thousands.

The ‘second summer of love’ – which oddly covers the summers of both 1988 and 1989 – then received the all-important media panic from the tabloids, essential to any underground scene going nuclear. In June 1989, the Sun, which had been knocking out their own smiley face t-shirts, suddenly cottoned on to what was actually going down at these massive events. The newspaper’s ‘Spaced Out’ headline, detailing the drugged-up antics witnessed at a Sunrise rave in Berkshire, was UK rave’s equivalent of the Daily Mirror’s ‘The Filth And The Fury!’ that followed the Sex Pistol’s potty-mouthed appearance on Bill Grundy’s tea-time talk show Today. Now, even your nan knew about acid house.

The party carried on right through to the end of the scorching summer of ’89, when Manchester’s A Guy Called Gerald (Gerald Simpson) released Voodoo Ray, which went on to be the biggest-selling independent single of that year. Acid house was largely over, but rave was continuing to grow as Detroit techno and new beat from Belgium started to mix it up with the vibes.

At a time when big-name rock, post-Live Aid, had Madonna, Prince, Michael Jackson, Bruce Springsteen, Dire Straits and U2 filling sports stadiums night after night, here was an enormous cultural movement with an almost total absence of celebrity. Even the records arrived in plain sleeves with little or no information. The more obscure a track was, the better. Whether you were pilled to the eyeballs or not, the hypnotic music and the overwhelming vibes transformed the most depressing abandoned cement factory into Studio 54. The audience was front and centre of this mushrooming scene.

Many women have talked about the freedom of being able to mix with men at these raves with absolutely zero agenda. Men no longer needed shiny shoes, pressed trousers and a collared shirt to get on to a dancefloor; a place rendered much less intimidating while rushing on E. Men, women, straights, gays, blacks and whites partied together as the establishment played catch-up with a totally renegade underground scene that was spilling out into the mainstream.

Rave was far from being a Utopia, but it was for many, a year zero. The rave scene established it own sense of community, built from the ground up. Fanzines and magazines popped up alongside fledgling record labels as the entire UK music industry was turned on its head. There were one-hit wonders, nom-de-plumes, collaborations, collectives, DJs who made music, musicians who DJed. The scene was making massive strides with virtually nobody in control. There were no agents, managers or sponsors in those early days.

Pirate radio burst into life too, as the dial became a battleground for rival stations. Record shops had counters piled high with flyers for upcoming events while new clothes labels and shops meshed the hippy ethnic vibe with rare-groove chic and the brash peacock colours of the soccer casuals, many of who had deserted the terraces to go raving.

Indie bands and fans joined in, with Stone Roses and the Paul-Oakenfold-produced Happy Mondays taking rave into completely new realms on Top of the Pops. New Order released Technique (recorded in Ibiza) in 1989, which was drenched in Vitamin D and a million miles away from their previously, more introverted sound. Stone Roses’ Spike Island gig, the following year, represented peak Madchester with a line-up that featured New York’s Frankie Bones and Hacienda’s resident DJ Dave Haslam. That same summer, the notoriously stuffy stiffs at the Football Association commissioned New Order to record England’s official World Cup song for Italia ’90, the tournament that was to reboot the national game following some of its darkest days.

The official England World Cup track, World In Motion, was straight from the dancefloor, complete with a loved-up message of hope. There were smiley faces all round. Unless you were Paul Gascoigne.

By 2002, the whistles and Reni hats of rave long packed away, another era-defining revolution was due. But at the film screening, not even Anthony H Wilson could come up with a pertinent answer as to what it might be. Grunge? Nu-metal? Surely not.

The answer was staring us in the face. In 2001, Apple invented the iPod. Rave had put machines front and centre. Now they were taking over.